|

Home >> Shipwrecks & Gold

Shipwrecks In The U.S.

In the United States, there are actaully many shipwrecks that occured over the past several centuries. Specifically off the coast of North Carolina. In the United States, there are actaully many shipwrecks that occured over the past several centuries. Specifically off the coast of North Carolina.

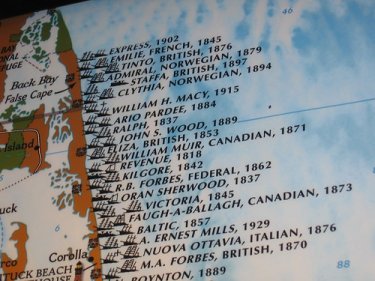

There is a reason why the coast of North Carolina is known as the "Graveyard of the Atlantic." More than 2,000 ships have sunk in these waters since people began keeping records in 1526. After all, the Outer Banks is the spot where the cold waters of the Labrador Current, which originates around the coast of Norway, collide with the warm waters of the Gulf Stream.

In addition, shifting underwater sand bars, the Diamond Shoals, conspire to send ship after ship to the depths of the Atlantic. And while we may think that all of the fighting during World War I took place in Europe or in the Pacific, German U-boats added hundreds more ships to the lists of casualties from 1915 to 1919.

The Outer Bankers (the correct way to refer to residents of the Outer Banks) did not give up in the face of such adversity. Before the Coast Guard existed, lifesaving stations, wooden shanties where diligent and hardy men would keep watch out for endangered ships, dotted the shore. At the Chicamacomico Lifesaving Station, located 15 miles south of Oregon Inlet at Rodanthe, six men saved the lives of 42 men of the British frigate, the Mirlo, when a German U-boat surprised our allies. Only 11 Crosses of Honor have ever been awarded in this country. The men of Chicamacomico hold six of them. The restored station reenacts drills every Thursday during the summer months.

Spanish Shipwrecks

Throughout the Spanish colonial period ships were lost at sea. Just during the period of the early explorers there are 39 known wrecks involving at least 110 vessels, from the sinking of Columbus's ship the Santa María in the Bay of Caracol, Hispaniola in 1492 through the loss of the ship Santiago by Magellan at Rio de Santa Cruz and Cortés's loss of three ships at Veracruz, both in 1520. Of the hundreds of Spanish colonial shipwrecks from the sixteenth through the eighteenth centuries, only a few were "treasure ships" containing a significant number of items of numismatic value. These "treasure ships" were making their return journey to Spain filled with gold, silver, coins, jewels and products from the new world. Below is a brief list of the more significant treasure ship wrecks. Throughout the Spanish colonial period ships were lost at sea. Just during the period of the early explorers there are 39 known wrecks involving at least 110 vessels, from the sinking of Columbus's ship the Santa María in the Bay of Caracol, Hispaniola in 1492 through the loss of the ship Santiago by Magellan at Rio de Santa Cruz and Cortés's loss of three ships at Veracruz, both in 1520. Of the hundreds of Spanish colonial shipwrecks from the sixteenth through the eighteenth centuries, only a few were "treasure ships" containing a significant number of items of numismatic value. These "treasure ships" were making their return journey to Spain filled with gold, silver, coins, jewels and products from the new world. Below is a brief list of the more significant treasure ship wrecks.

The earliest recorded treasure wreck is from 1544 when three out of a fleet of four merchant ships carrying new world products, including gold and silver, sank off the coast of Padre Island, Texas (near Port Mansfield) during a violent storm. Of the three wrecks the Santa María de Yciar, was destroyed in the 1940's during the dredging of the Mansfield Cut (a channel through Padre Island linking the Gulf of Mexico with the Laguna Madre and the coast of Texas) and the Espíritu Santo was ruined by treasure hunters in 1967. The third ship, the San Estebán, has been carefully excavated by the Texas Archeological Research Laboratory. Its contents are the oldest cataloged remains of a treasure ship, containing a gold bar and silver bullion as well as Spanish colonial silver coins. As with all treasure wrecks part of the contents was lost at sea during the time of the wreck (usually during a hurricane). Also, usually within a few weeks of the disaster, the Spanish sent Indian divers into the ocean to salvage as much treasure as possible. These events as well as the ravages of the sea over time have left only a portion of the full contents of the treasure ships for modern exploration.

In 1596 the merchant ship San Pedro, transporting a cargo of gold, silver and jewelry to Spain, sank on Bermuda's inner reef. Among the treasures recovered was a gold pectoral cross with seven emeralds said to be one of the most valuable pieces of jewelry recovered from any Spanish shipwreck. The cross was on display in the Bermuda Maritime Museum, however in 1975 when it was removed from its case during a royal visit it was discovered the cross has been stolen and replaced with a plastic replica!

In the following century the Spanish merchant ship, called a naos, was supplemented with a larger and more heavily armed vessel called a galleon. The earliest recovered galleon is the Nuestra Señora de Atocha, which left Cuba for Spain in September of 1622 as vice flag ship of a fleet of 28 ships. The vessel was discovered about 70 miles off Florida near the Marquesas Keys in 1985 by Mel Fischer with its treasure of gold and silver bars and coins intact.

In 1641 a converted merchant ship, La Concepción, left Havana filled with valuable cargo to be taken to Spain, including some 60,000 coins. The ship was discovered in 1978 in an area known as the "Silver Bank" off the coast of Hispaniola, near present day Puerto Rico (Hispaniola was the name for the island between Cuba and Puerto Rico, which is now divided between Haiti and the Dominican Republic).

In 1715 a fleet of eleven galleons carrying gold and silver, valued at almost fifty six million reales, was struck by a hurricane off the east coast of Florida near the mouth of the Saint Sebastian River not far from present day Cape Canaveral. The ships broke apart and sank off the coast between Melbourne and Stuart with their cargo scattered over the ocean floor. To date five of the wrecks have been located and much treasure from this fleet has been recovered from the ocean bottom.

In 1733 a fleet of four galleons and eighteen merchant ships left Havana loaded with cargo. The fleet hit a hurricane in the Florida Keys and was disbursed and sunk over an eighty mile area. Spanish authorities immediately sent out salvage crews who were successful in recovering much of the gold and silver. Several of these ships have been located in modern times; they continued to yield gold, silver and coins, including the five gold bars displayed in this website.

References

For additional information see: Roger C. Smith, "Treasure Ships of the Spanish Main: The Iberian-American Maritime Empires," in Ships and Shipwrecks of the Americas: A History Based on Underwater Archaeology, edited by George Bass, London: Thames and Hudson, 1988, pp. 85-106 and Donald H. Keith, "Shipwrecks of the Explorers," in the same volume on pp. 45-68. For an account of the 1715 fleet see: Robert F. Burgess and Carl J. Clausen, Gold, Galleons and Archaeology: A History of the 1715 Spanish Plate Fleet and the True Srory of the Great Florida Treasure Find, Indianapolis: Bobbs-Merrill, 1976

|